The Official online home of TAGSRWC

|

July 96

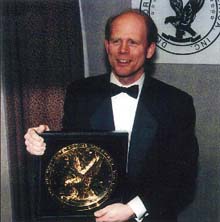

Ron Howard Weightless Again Over Apollo 13's Directors Guild of America (DGA) Win

photos by Robert Markowitz, Don Perdue, Ron Batzdorff

There are pivotal moments in everyone's life, those times when a choice is made that sets the course of one's personal destiny. Most of us, however, are given the benefit of at least a decade or two of kid stuff before we begin our journey in earnest. For Ron Howard, the defining moment came at the age of five, and the crucial decision was made for him by his father.

The surprise winner of the DGA's 1995 Outstanding Feature Film Directorial Achievement Award for his work on the real life space odyssey of Apollo 13 was already a veteran of stage and screen by 1960 when Sheldon Leonard sought out the precocious redheaded kid he had seen in a failed television pilot with Bert Lahr. One of the many highlights of Leonard's storied career, the Guild's longtime secretary-treasurer, was at that time creating a situation comedy series that was destined to become one of television's all-time classics, The Andy Griffith Show.

|

Griffith's character, Sheriff Andy Taylor, was a widower with a young son named Opie and Leonard felt young Ronny Howard would be a perfect fit, but the boy's father Rance was hesitant to permit the professional commitment required by a television series. It was only after Leonard gave his personal reassurance that Ronny would not be deprived of his childhood if allowed to join the Griffith Show that the elder Howard relented.

"I've often wondered," recalled Leonard today, "what would have happened to Ronny if his father had refused to let him play Opie."

Ron Howard chuckled at that story while driving home from the first day on the set of his latest movie, Ransom, following his DGA Award triumph. "Sheldon was true to his word," he said. "They often rearranged the shooting schedule so that I could go play in Little League or whatever. It was fantastic."

Thus began one of the most successful journeys in show business history. Opie Taylor became an icon of all-American boyhood for the generation growing up in the turbulent 1960s, and child star Ronny Howard grew into respected film director Ron Howard.

The DGA win is the sweetest career affirmation yet for Howard. "In the last few years, my sensibilities began changing, or maturing, and since about the time I did Parenthood, I seem to be first and foremost interested in exploring human experiences," he explained.

One human experience often noted by critics as the hallmark of Howard's directorial work is its consistency of entertainment value. "One of the reasons I became a director is because I didn't want to be typecast, and as an actor I was probably always going to be," said Howard. "As a filmmaker, I tried to make it an objective early on not to become categorized too quickly."

With an impressively diverse series of films over the past decade, including Splash, Cocoon, Parenthood, Backdraft, Far And Away, The Paper and Apollo 13, Howard has firmly established himself among the top rank of feature film directors working today. But he still views directing as a process of discovery. "One of the great things about being a director as a life choice is that it can never be mastered," he said. "Every story is its own kind of expedition, with its own set of challenges."

Filming the

star-crossed story of the Apollo 13 mission presented Howard with a series

of particularly unique challenges. "I never counted on Apollo 13 being

a thriller because people would already know the outcome," the director

explained. "The one thing we knew we could do is offer the audience the

experience of what it was like to live through the Apollo 13 mission, and

I believed that would be a compelling reason to make the movie and a compelling

reason for people to want to see it."

Filming the

star-crossed story of the Apollo 13 mission presented Howard with a series

of particularly unique challenges. "I never counted on Apollo 13 being

a thriller because people would already know the outcome," the director

explained. "The one thing we knew we could do is offer the audience the

experience of what it was like to live through the Apollo 13 mission, and

I believed that would be a compelling reason to make the movie and a compelling

reason for people to want to see it."

Howard committed to directing Apollo 13 even "knowing that there really was no handle going in on how to make weightlessness look realistic." He wasn't too concerned, however, since he had the similar experience while doing Backdraft of being forced to find new ways to film fire. He believed that they could ultimately find a way to portray space realistically.

"I was talking with Steven Spielberg about the problem during pre-production, and we discussed possibly filming underwater, but that wasn't going to work," Howard continued. "Then we got to talking about using the KC-135 airplane which creates 23 seconds of weightlessness by climbing and diving sort of like a roller coaster. I had been thinking about it, and Steven urged me to check it out, and that's what we ended up using in the film."

The director and his leading actors had to pass rigorous written exams and physical tests before officials would allow them to even take a test ride in the KC-135. "The NASA people, I think, were impressed by our professionalism, and in the end it all worked out great."

Solving the "where to film space" problem opened up a whole new series of challenges, however, regarding lighting, sound and how to give directions while weightless. Matching the angles and composition from previously filmed sequences required "seamless illusions" in order to maintain the credibility of the story.

"Story is king," Howard responded without hesitation when asked about his priorities in selecting projects to direct. "The greater achievement in Apollo 13 was not the technological stuff," according to Howard. "It was in developing a flow to the story through which we were able to blend the three environments of home, Mission Control and the capsule in a way that allowed the sequences to build and communicate the danger, the sacrifice, the courage and the emotional stress that these people were feeling without resorting to situations where the characters would be saying things they would never say in real life."

Howard further explained that, "While trying to avoid self-conscious camera movement or cinematic trickery, I was constantly looking for ways to communicate a feeling with a composition or a camera move to help the audience understand what was going on with these actors. They couldn't overplay their hand and sell out that straight-faced, composed astronaut behavior.

"I learned a hell of a lot about the psyche of a test pilot," he admitted. "It's not that they ignore fear, but they have dealt with it so many times, they actually come to expect moments where the natural inclination is going to be to panic and they have trained themselves not to waste precious seconds on panic, but to feel fear, even embrace it. And then, almost like tai chi or something, they sort of let that go through them and work right through the problem. They realize that panic is their enemy."

Howard's motivation for wanting to do Apollo 13 changed along the way. "Initially, I embraced it as an irresistible directorial challenge," he said. "How could we somehow bring this thing to the screen in a way that audiences had not seen or experienced before?"

He cited the difficulties faced in making the highly sophisticated vocabulary used by scientists translate into meaningful words for a general audience. "NASA-speak is very specific to the scientific and technical issues of space travel," Howard explained. "All of us involved in the production were constantly combing through the NASA transcripts, searching for ways to communicate some very basic human emotional ideas while utilizing what is, for all intents and purposes, a foreign language."

As an example, the Guild's newest feature film award-winner offers the crucial moment in his film when Tom Hanks as mission commander Jim Lovell is told by Mission Control in Houston that in order to survive, the astronauts must "shut down the react valve," an action that means Lovell's dream of landing on the moon will be lost forever. "We had to make lines like that into turning points in the story," he pointed out. "The audience had to be able to understand that this was a heartbreaking moment for Jim Lovell. Apollo 13 is a survival story, but it's also a story about someone who doesn't get his dream."

In order to accomplish the feat, Howard explained that the film

first needed to "use the scientific jargon effectively, then find a way to

translate it and thereby educate the audience, and finally, use the jargon

as a story point." His solution was "in a way, to make a silent movie with

this film" and stay on the lookout for new ways to communicate the emotion

of the moment.

In order to accomplish the feat, Howard explained that the film

first needed to "use the scientific jargon effectively, then find a way to

translate it and thereby educate the audience, and finally, use the jargon

as a story point." His solution was "in a way, to make a silent movie with

this film" and stay on the lookout for new ways to communicate the emotion

of the moment.

With his Apollo 13 victory, Howard earned membership in the very exclusive club of DGA Theatrical Direction Award-winners with the likes of Mankiewicz, Stevens, Ford, Zinnemann, Kazan, Mann, Lean, Minnelli, Wyler, Wilder, Wise, Cukor and Coppola, to name a few. "It was a thrill to be nominated by the DGA. And, of course, very gratifying," he said.

Apollo 13 also received nine Academy Award nominations, including one for Best Picture, but the director's name was conspicuously missing from the list. Howard's reaction to the perceived snub is measured and thoughtful, "A lot of directors that I've talked to over the years -- winners, losers, those never nominated -- really do look to the DGA Award as the one," he said. "As much as everyone in Hollywood wants to be a part of the grand tradition of the Oscar Show -- and I do, too -- in a really pure sense, the DGA Award is the most coveted because it's from your peers."

With this year's DGA triumph, Ron Howard becomes only the fourth director since the Guild competition began in 1949 to win the DGA Award and not go on to take home the Best Director Oscar. The last time it happened was 1985, the same year as Howard's only previous DGA nod, for Cocoon. The winner that year, however, was Steven Spielberg, another director whose picture, The Color Purple, was nominated for multiple Oscars -- including Best Picture -- but he himself was overlooked by the Academy. The only previous instances that the DGA trophy winner hasn't collected an Oscar as well occurred in 1972 when the Guild chose Francis Coppola's The Godfather while Oscar liked Bob Fosse's Cabaret, and initially in 1968 when Anthony Harvey won the DGA award for The Lion In Winter while Carol Reed took home an Oscar for Oliver!

(In the early days of the DGA's Awards program, the Guild's second winner, Robert Rossen's All The King's Men lost the Oscar to first Guild honoree Joseph L. Mankiewicz's A Letter To Three Wives when different Academy and Guild eligibility requirements forced both directors into the same Oscar pool.)

Howard's entry into such august company comes as no surprise to Leonard, who recalled, "From the age of five or six, Ronny sat in on our script readings when we would go over them to determine what repairs were needed. He recently told me that those readings were the start of his knowledge that there was something beyond the acting in what we were doing. Today, Ron Howard is a remarkable young man with a great sense of story and a great talent for working with actors."

Howard returned the compliment while detailing the origins of his directorial methodology: "I try to create an environment that is not so different from the one that I experienced on The Andy Griffith Show, where people were clearly open to new ideas. There was a kind of on-going collaboration between the writers, producers, directors and all of the cast members -- and they even included me in that from a very early age. Consciously or unconsciously, I've brought that same spirit to my work as a director."

As to the future, Howard's ambitions are "to stretch even more as a director, to learn more about making movies, and to broaden the scope of my understanding and ability for cinematic undertakings."

He attended the DGA's 48th Annual Awards banquet in New York City with fellow nominees Ang Lee (Sense & Sensibility) and Mike Figgis (Leaving Las Vegas), while nominees Mel Gibson (Braveheart) and Michael Radford (Il Postino) were in Los Angeles for the Guild's west coast celebration.

"I wasn't expecting to win," Howard concluded. "I told my wife when we were driving home after I won the DGA Award that it was almost like being weightless again."

Charles S. Warn is the Guild's National Executive in Charge of Communications & Public Affairs.

| Ron Howard Directing Credits |

| Grand Theft

Auto (1978) Cotton Candy (for television) (1978) Skyward (for television) (1980) Through the Magic Pyramid (for television) (1981) Night Shift (1982) Splash (1984) Cocoon (1985) Gung Ho (1986) Willow (1988) Parenthood (1989) Backdraft (1991) Far And Away (1992) The Paper (1994) Apollo 13 (1995) Ransom (1996) |